We have been interviewing recently-both for a new partner and a lead nurse to replace two team members seeking the hallowed ground of retirement. We thought long and hard about appropriate questions to ask to bring out the best in the candidates, and we are very happy with our chosen replacement colleagues. I was keen to ask the question “Describe yourself in three words”, as I was hoping for someone to be brave enough to answer “Succinct”. In the end this question did not feature, but I think it could have told us an awful lot about the individuals, and even their consulting styles.

We all have different consultation techniques, finely honed over the years and constantly undergoing change. I would probably describe mine as “minimalist”-rather like conversations with my wife where I have learnt to say little, listen carefully, nod and grunt at appropriate times and leave the door open for further discussion if needed. I feel comfortable in this role, but it is perhaps more a reflection of my natural persona than any learned technique-some of my more verbose partners will consult very differently and our patients of course will often select where they feel most understood, so it is nice to have such variety in the practice.

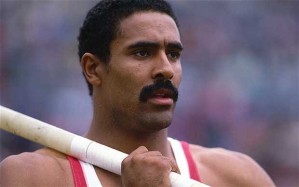

Just occasionally I get shaken out of my comfort zone, and this is often when the tables are turned, and the person sitting in front of me starts asking me the questions. “Hang on a minute” I think, “I’m Paxo, not you” (Can you imagine him as physician…? )

I was recently stumped by a patient I was counselling about a vasectomy, when he suddenly asked me “Have you had one doc?”

Where do you start when answering that-a straight yes or no would be perhaps the easiest way, but the implications of the enquiry go much further. What might they ask next-“I’m struggling with the fall out of my affair, have you ever had one doc”? This type of questioning almost takes the conversation out of the consulting room and into the pub, a few mates sitting around having a drink and picking over marital difficulties-that’s not where I see myself with patients, but maybe it is an indication of them feeling confident in asking for advice. There are no set boundaries for the patients in the consulting room of course-just social convention and we can learn a lot about patients from the questions they ask.

The obvious Catch 22 question I think is “What would you do doctor?” The almost impossible question to answer-trying to separate my own learned experiences and medical knowledge, from the patient’s. Despite having a broad overview of the evidence behind medical treatments, it is very difficult not to let individual observations affect my decision making process, and distill that to answer the question I think the patient is trying to ask, with reference to their own particular circumstances, not mine.

Would I take medication to turn my yellow toenails clear again? No-not after I have seen one nasty medication induced hepatitis I wouldn’t, but I’m not the 19 year old flip flop model looking for work so that’s quite a tricky one to answer…

In general, as a patient I would be inclined to do very little, take very few treatments, and rely heavily on nature taking its course, particularly in acute illness. In reality, some patients take a different view on life, and here I will just try and present the pros and cons of treatment (or not) as best I can. The really tricky ones are where the benefits of treatment are not clearcut-for example with palliative chemotherapy. What would I do? I really don’t know, and as there are so many differences in our situations, I also don’t know what you (the patient) should do-but we will sit down and work through it together.

So what to do the next time a patient says “Can I ask you a question?”

Run for cover? If they ask me “What would you do doc?” I will give them the best answer I can think of…

“Well I would ask my doctor of course.”